Array

(

[thumbnail] => https://s42831.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/whose_endless_war_in_afghanistan_image-150x150.jpeg.optimal.jpeg

[thumbnail-width] => 150

[thumbnail-height] => 150

[medium] => https://s42831.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/whose_endless_war_in_afghanistan_image-300x199.jpeg.optimal.jpeg

[medium-width] => 300

[medium-height] => 199

[medium_large] => https://s42831.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/whose_endless_war_in_afghanistan_image-768x510.jpeg.optimal.jpeg

[medium_large-width] => 768

[medium_large-height] => 510

[large] => https://s42831.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/whose_endless_war_in_afghanistan_image-1024x680.jpeg.optimal.jpeg

[large-width] => 1024

[large-height] => 680

[1536x1536] => https://s42831.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/whose_endless_war_in_afghanistan_image-1536x1020.jpeg.optimal.jpeg

[1536x1536-width] => 1536

[1536x1536-height] => 1020

[2048x2048] => https://s42831.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/whose_endless_war_in_afghanistan_image.jpeg.optimal.jpeg

[2048x2048-width] => 2048

[2048x2048-height] => 1360

[gform-image-choice-sm] => https://s42831.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/whose_endless_war_in_afghanistan_image.jpeg.optimal.jpeg

[gform-image-choice-sm-width] => 300

[gform-image-choice-sm-height] => 199

[gform-image-choice-md] => https://s42831.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/whose_endless_war_in_afghanistan_image.jpeg.optimal.jpeg

[gform-image-choice-md-width] => 400

[gform-image-choice-md-height] => 266

[gform-image-choice-lg] => https://s42831.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/whose_endless_war_in_afghanistan_image.jpeg.optimal.jpeg

[gform-image-choice-lg-width] => 600

[gform-image-choice-lg-height] => 398

)

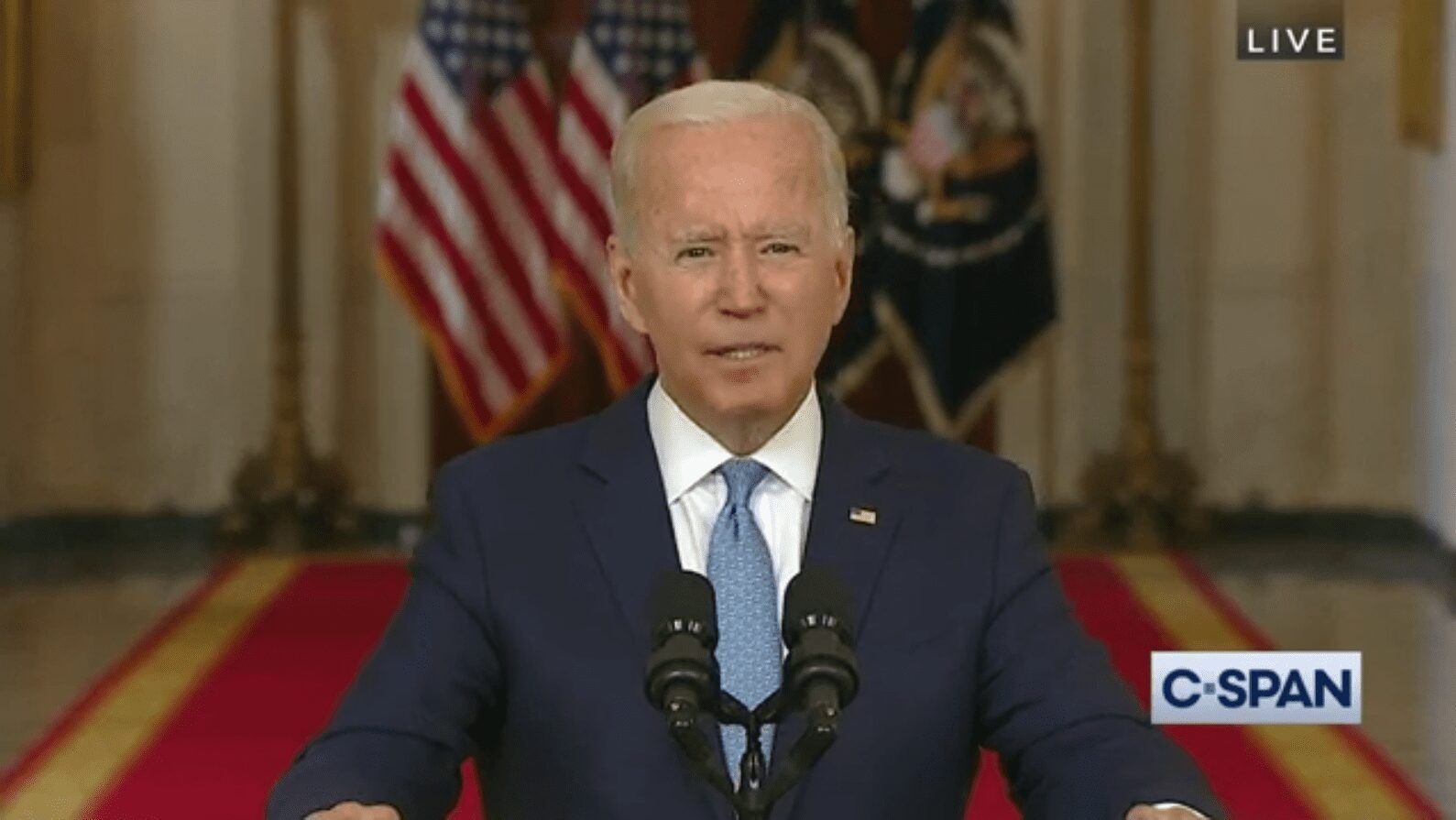

Whose endless war in Afghanistan is ending?

Be glad that Americans will soon be out of harm’s way. Accept the argument that the homeland will no longer be at risk from Afghanistan-based terrorists, and even acknowledge that we weren’t certain to accomplish anything more by staying on. But let’s not say Afghanistan’s war is over.

The Biden administration’s April 14 announcement that all troops will depart Afghanistan by September 11, 2021 set off a round of recalculations in the region. It was no surprise that the Taliban immediately withdrew from the planned Istanbul meetings and that peace talks are now “on hold.” It also set off a wave of punditry here in the US.

Given past American missteps, misleading communications, and poorly executed policies over the last twenty years under three different administrations, skepticism about what could be accomplished through an extended presence was understandable. The Trump administration’s February 2020 commitment to the Taliban to remove all US forces by May 2021 left the incoming administration with a poor set of options.

Yet, the Biden team seems to have largely brushed aside the recommendations of the Congressionally-mandated, bipartisan Afghanistan Study Group to strengthen the admittedly fitful Doha negotiations “to give the peace process sufficient time to produce an acceptable result,” instead deciding on a condition-less withdrawal by September 11, itself a puzzling deadline.

Now, with the US and NATO on their way out, the Taliban (and their Pakistani backers) have no reason to negotiate. And we have now begun one of the few things that nearly everyone agreed should be avoided–a precipitous withdrawal.

The US relationship with Afghanistan has always been complicated, and great minds (and pundits) may differ on the wisdom of staying on. This is understandable. What is less understandable is the misleading rhetoric about how the “forever war” is ending. Certainly, thirty-four million Afghans would beg to differ. For them, war between the Afghan security forces and the Taliban and other insurgents continues. For some, the war may be just beginning.

Proclamations from officials (e.g., “We need to close the book on a twenty-year war;” “it was an easy decision”) and from pundits (e.g., the factually incorrect “The Afghanistan War Has an Official End Date,” and the crowing “We ended an endless war today!”) seem at odds with reality. US and NATO troops will be departing Afghanistan, but under any plausible scenario, the war will go on. More likely, it will escalate. Without the restraining presence of the US and its allies, neither side will feel any pressure to compromise or enter a power-sharing deal. An emboldened Taliban is likely to press for military victory, while the Afghan government will continue to face an existential threat.

Since the February 2020 troop withdrawal agreement (parts of which remain obscure), the Taliban have tactically refrained from attacking US facilities and personnel, while targeted assassinations and attacks on minority ethnic groups, civil society advocates, professional women, journalists, and others whom the Taliban and similar-minded groups consider a threat to their prospective order, have increased. There is already evidence that various political-military-ethnic groups are arming (or rearming) themselves and preparing for resistance and potential civil war. Ironically, the argument that “Afghanistan is a different country now” increases the likelihood of continued bloodshed, as those with a stake in that new country will resist giving it up without a fight. Large numbers of others will continue to flee the country and become refugees in the region and beyond, many through human trafficking networks as borders are officially closed to them.

The Biden administration has pledged to remain engaged in Afghanistan and to use our “full toolkit” to support the Afghan defense forces, and provide civilian and economic assistance. But it remains to be seen what is in that sack without effective mechanisms for delivery and oversight, when whole regions already cannot be accessed due to conflict, or when Afghan authorities oppose elements of that assistance. As Representative Tom Malinowski (D-NJ) said recently, “That’s a story we tell ourselves to feel better about leaving.”

Administration officials in part may be hoping for a “Taliban 2.0”: that Taliban leaders have changed their ways, and that desperation for the international recognition and funding denied to them in the 1990s gives the US leverage–a thin reed of hope indeed.

Down the road, one can easily see where cutting off aid to a Taliban-influenced or dominated government that fails to stop illicit drug production and uphold human rights becomes a statement of our moral principles or, in the case of drugs, a requirement of legally binding commitments enacted by Congress.

Afghans saw a version of this movie in 1992, the last time we considered the Afghan war over—with the fall of the Soviet-installed government, the US largely forgot about Afghanistan until September 11, 2001. Now, with the war again “over,”—for Americans—it remains to be seen whether the US will continue to invest sufficient attention and political capital in yet another foreign conflict.

Claiming that the war is over while trying to take the moral high ground obscures the reality of ongoing conflict. Whether or not we have a moral obligation to fix what we contributed to breaking, US officials at least should be honest with the American public about what this isn’t. It isn’t the end of the Afghan war.

Photo: A U.S. Army Soldier in the Nangarhar province of Afghanistan. November 2007. (U.S. Air Force /Staff Sgt. Joshua T. Jasper)

More Resources

-

-

What Afghanistan Needs for the UN Global Ceasefire to Succeed

Said Sabir Ibrahimi

Stay Connected

Subscribe to our newsletter and receive regular updates on our latest events, analysis, and resources.

"*" indicates required fields