Array

(

[thumbnail] => https://s42831.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/bamiyan-min-150x150.jpeg.optimal.jpeg

[thumbnail-width] => 150

[thumbnail-height] => 150

[medium] => https://s42831.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/bamiyan-min-300x200.jpeg.optimal.jpeg

[medium-width] => 300

[medium-height] => 200

[medium_large] => https://s42831.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/bamiyan-min-768x512.jpeg.optimal.jpeg

[medium_large-width] => 768

[medium_large-height] => 512

[large] => https://s42831.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/bamiyan-min-1024x683.jpeg.optimal.jpeg

[large-width] => 1024

[large-height] => 683

[1536x1536] => https://s42831.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/bamiyan-min-1536x1024.jpeg.optimal.jpeg

[1536x1536-width] => 1536

[1536x1536-height] => 1024

[2048x2048] => https://s42831.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/bamiyan-min-2048x1365.jpeg.optimal.jpeg

[2048x2048-width] => 2048

[2048x2048-height] => 1365

[gform-image-choice-sm] => https://s42831.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/bamiyan-min-scaled.jpeg.optimal.jpeg

[gform-image-choice-sm-width] => 300

[gform-image-choice-sm-height] => 200

[gform-image-choice-md] => https://s42831.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/bamiyan-min-scaled.jpeg.optimal.jpeg

[gform-image-choice-md-width] => 400

[gform-image-choice-md-height] => 267

[gform-image-choice-lg] => https://s42831.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/bamiyan-min-scaled.jpeg.optimal.jpeg

[gform-image-choice-lg-width] => 600

[gform-image-choice-lg-height] => 400

)

Next Steps for the Afghan Peace Process

Afghanistan, along with the rest of the world, faces major uncertainty from the COVID-19 pandemic—a shock that complicates this assessment of the Afghan peace process and the challenges that lie ahead.

After nearly two years of formal negotiations, the United States and the Taliban signed an “Agreement for Bringing Peace to Afghanistan” in Doha, Qatar on February 29, 2020. The agreement covers four main topics: the withdrawal of US troops; counter-terrorism cooperation between the US and the Taliban; a reduction in violence that can lead to a ceasefire; and the initiation of the intra-Afghan negotiations. The agreement paves the way for intra-Afghan talks between the Taliban, the Afghan government, and other political factions—a step that the Taliban had refused to take until an agreement with the US was secured. Simultaneously, the US and Afghan governments announced a joint declaration paving the way for condition-based withdrawal of US forces. While the agreement is a breakthrough, the peace process faces significant challenges—which are likely to be exacerbated by the spread of the coronavirus in Afghanistan and neighboring countries.

The first hurdle is the post-presidential election crisis in Kabul. On March 9, two separate inauguration ceremonies were held in Kabul, one by President Ashraf Ghani and the other by Chief Executive Abdullah Abdullah. The international community has largely supported Ghani, who was declared the winner by the election commission after securing 50.6% of the vote. Abdullah has contested the results as fraudulent and hosted his own swearing-in next door to the presidential palace. The US is mediating between the parties and called on them to create “an inclusive government,” and other Afghan political leaders, such as former president Hamid Karzai, are also mediating. Representatives of Ghani and Abdullah have met, but they have yet to agree to a resolution.

The election crisis has also complicated the prospect of finalizing a negotiating team and determining an agenda for negotiations. The president’s office has stated that they have finalized a list, but it has yet to be made public. However, opposition political parties and Afghan civil society also want a voice in the negotiation process and representatives on the team. Abdullah has said that his team will enter into negotiations without any preconditions, whereas Ghani favors conditions such as a ceasefire and gradual release of the Taliban prisoners. The US-Taliban agreement mentions a prisoner exchange of up to 5,000 Taliban inmates for 1,000 prisoners from the Afghan government side, but Ghani said that a swap of that scale would require more time and offered a gradual release of 1,500 prisoners as a confidence-building measure, which the Taliban have rejected. As there are more than 5,000 Taliban prisoners in the custody of the Afghan government, the issue will remain a factor in intra-Afghan negotiations, in addition to discussions around reintegration, a permanent ceasefire, transitional justice, women and minority rights, and possible constitutional amendments.

The success of the talks will also depend on the actions of regional stakeholders. Neighboring countries all claim to want peace in Afghanistan, but on their own terms. Pakistan has long provided political support and safe haven to the Taliban. The US-Taliban agreement does not address this matter, but the US-Afghan joint declaration acknowledges it, stating that the US “commits to facilitate discussions between Afghanistan and Pakistan to work out arrangements to ensure neither country’s security is threatened by actions from the territory of the other side.” Pakistan played a key role in facilitating US-Taliban talks, and remains crucial for the success of the intra-Afghan talks. While Afghanistan has provided assurances that Afghan territory will not be used against its neighbors, Pakistan’s concerns about being encircled by India will remain an issue. Iran has supported peace negotiations, but retains its intelligence and diplomatic relations with the Taliban. The Iranian government called the recent agreement a tool for the US to “legitimize its troops’ presence in Afghanistan.” Russia has maintained contacts with the Taliban for many years, and signaled support for the agreement. China also supported the signing of the agreement, and Beijing has called for an “orderly and responsible withdrawal of foreign troops to avoid a power vacuum,” while seeking opportunities to include Afghanistan in its Belt and Road Initiative.

As the one-week reduction in violence came to an end, the Taliban resumed attacks on Afghan security forces. On March 3, Taliban conducted 43 attacks in Helmand, killing two police officers. On March 4, in attacks across the country, the group killed 4 Afghan civilians and 11 members of security forces, leading to counterattacks by Afghan and US forces. On March 16, the Taliban attacked a security checkpoint on the Herat-Ghor highway, killing at least 11 and losing 20. While there is a de facto ceasefire between the Taliban and the US, the allied forces in Afghanistan continue to provide military support to the Afghan security forces against Taliban attacks, which may jeopardize the agreement and the peace process.

The US-Taliban agreement is a necessary first step toward ending the conflict in Afghanistan, but it does not guarantee peace. The next critical stage will be the intra-Afghan talks, which should prioritize a ceasefire to reduce the violence. For the talks to succeed, Kabul will have to resolve the current political crisis and form an inclusive negotiating team. At the same time, regional actors will need to reach a consensus on peace in Afghanistan, and the US will need to withdraw responsibly. China, with its strong ties to Pakistan and close trade relationships to Iran, Russia, and Central Asia, can play a vital role in cementing that regional understanding. But all of these necessary steps will be complicated by coronavirus—for example, intra-Afghan dialogues were supposed to take place abroad, which may be impossible due to restrictions on travel and gatherings. With its health infrastructure weakened by the decades of conflict, Afghanistan will need support from the World Health Organization and the international community to weather this crisis and keep the peace process alive.

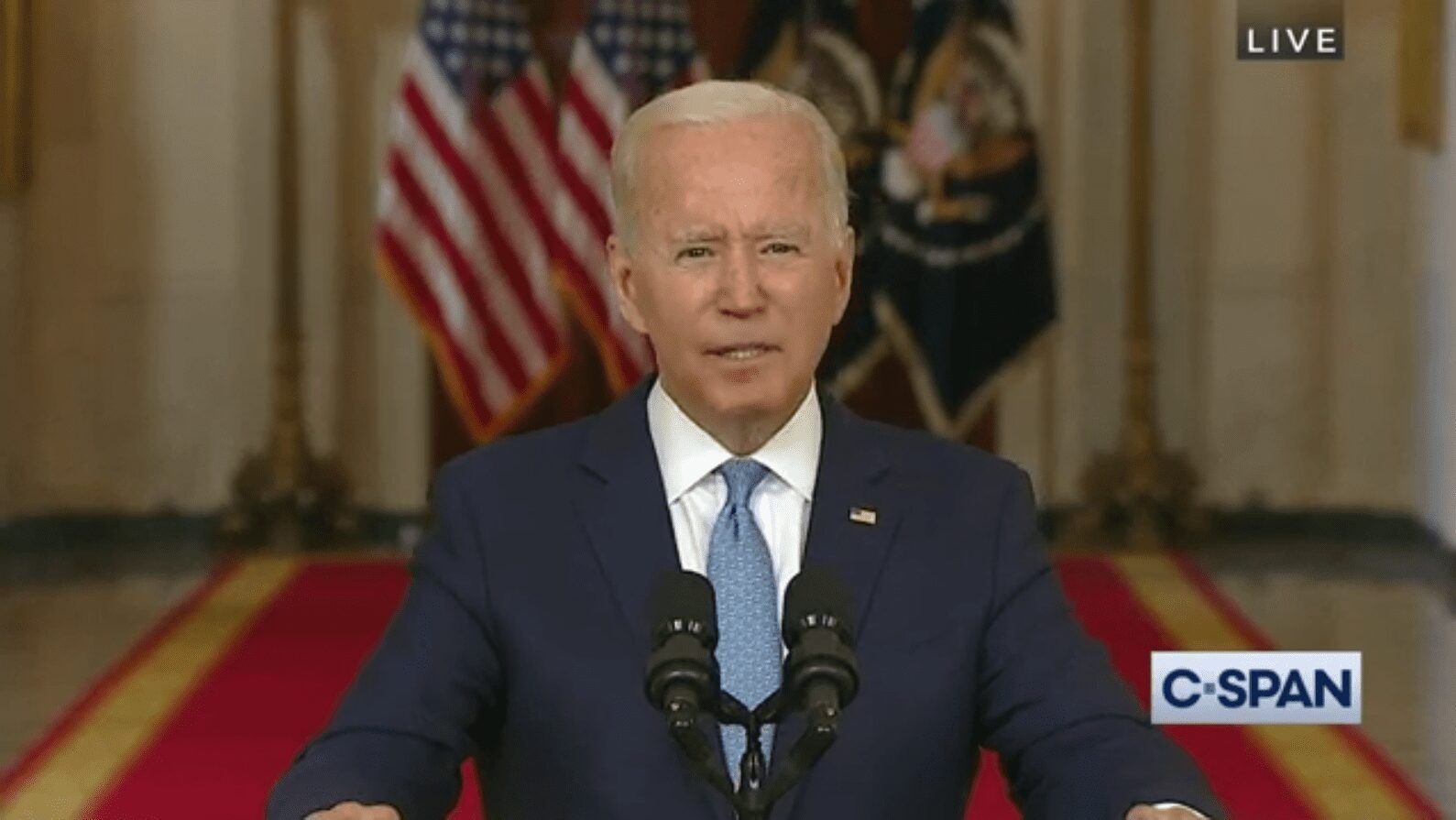

Photo: UN Deputy Secretary-General Amina Mohammed greets female deminers at a demining site in the province of Bamyan, Afghanistan in July 2019 (UNPhoto/Fardin Waezi).

More Resources

-

-

Whose endless war in Afghanistan is ending?

Paul Fishstein

Stay Connected

Subscribe to our newsletter and receive regular updates on our latest events, analysis, and resources.

"*" indicates required fields