In their new book Equal Opportunity Peacekeeping: Women, Peace, and Security in Post-Conflict States, Sabrina Karim and Kyle Beardsley go beyond the headlines on sexual exploitation and the numbers of women’s participation to ask how the culture of UN peacekeeping needs to change if gender equality in peace operations is to become an attainable goal. Sabrina Karim recently spoke with GPOR’s Jim Della-Giacoma about the book and the research on which it is based and what follows is an edited transcript of that conversation.

Jim Della-Giacoma (JDG): Your book opens with a description about how in some countries the foreign policy is becoming more feminist and the defense forces more gender equal. And yet you start with something of a skeptical tone as these changes are taking their time to come to UN peacekeeping. “Are blue helmets just for boys?”, as you ask in the provocative title of your first chapter?

Sabrina Karim (SK): We frame the book noting the positive trends since UN Security Council Resolution 1325 was passed, such as the Hillary Doctrine in the United States and Sweden’s feminist foreign policy. We suggest the UN has been a pioneer in promoting equality in security because of the multiple UNSC resolutions since 1325 in 2000. While they have got a head start, the book is focused on the current and future challenges. Our provocative question, “Are blue helmets just for boys?”, sets the tone for book that looks at overcoming these challenges. We give a nod to the progress and innovations related to gender equality that have occurred in UN peacekeeping operations since 2000, but we want to make sure we don’t get pigeon holed into seeing improved peacekeeping operations only in terms of increased women’s participation. Gender equality in UN peacekeeping operations needs more than just increased women’s participation; there needs to be cultural change.

JDG: What is the history of how some of these reforms that came from UNSC Resolution 1325 have been implemented by the UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO)?

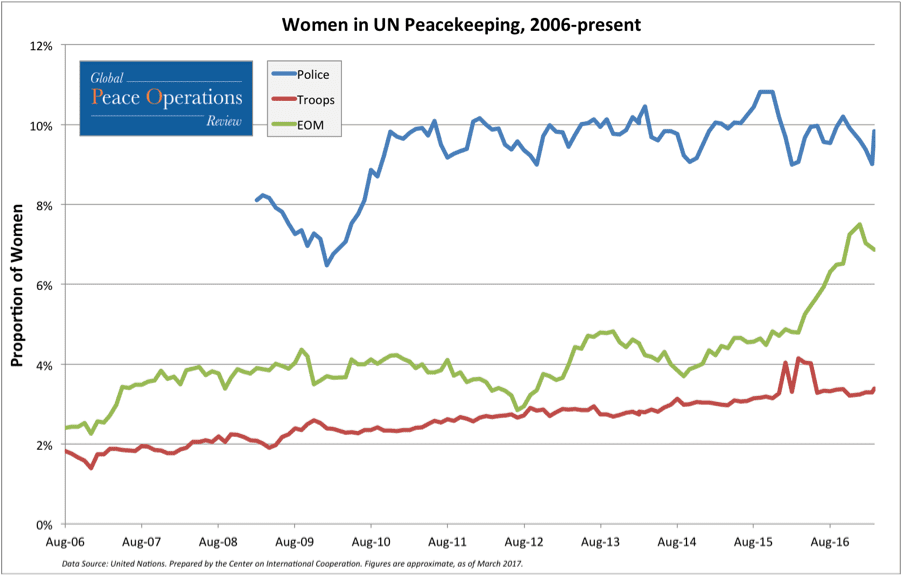

SK: Back in 2000, the vision of Resolution 1325 was centered on the three pillars of participation, protection and conflict prevention (though others might argue that there are more pillars). Our book focuses more on participation and protection, as there are still many challenges. Since 2000, there has been a call to increase women’s participation in peacekeeping operations. We didn’t see this become a mainstream issue that the UN Secretary-General talked about until after this resolution. For the past five years, the goal has been to try to increase women’s participation to 10 per cent in military contributions and 20 per cent in police contingents. These targets have not yet been met (see graph below). More recent data since book was written shows that trends might be improving, particularly related to female military observers who are close to meeting the 10 per cent goal. Moreover, you do see the issue of increasing women’s participation in some mandates, not all of them. Where there has been more movement is with the protection pillar, especially around sexual and gender based violence (SGBV). In several subsequent resolutions, such as 1820, 1888, 1889, and 1960, we do see a change in mandates with regards to SGBV and sexual exploitation and abuse (SEA) by peacekeepers along with the Zero Tolerance Policy in 2005. In 2015, we saw a move towards naming and shaming troop and police contributing countries whose personnel had been found to engage in sexual exploitation and abuse. With respect to gender mainstreaming, efforts have been a more confusing for policymakers in DPKO to operationalize. There is usually a civilian gender team and then there are also gender focal points in the military and police, usually women. Together, they are responsible for mainstreaming gender, even though it is sometimes unclear what this means. Individual missions have more discretion in how they operationalize this term.

JDG: What is the pattern of deployment for women in UN peacekeeping operations?

SK: Low participation of women in UN peacekeeping operations is something that is very widely noted, but in our book, we look beyond just the numbers to where female peacekeepers are deployed. We find that they tend to be in the safest missions and not necessarily where they are most needed. There are higher proportions of uniformed women peacekeepers in Kosovo and Liberia, instead of places like the CAR and DRC, where the UN has argued they are most needed because of the levels of sexual violence there. There is a gender protection norm, which is the idea that women still need to be protected even though they are in the military or police. This perception means they don’t end up being on the front lines where peacekeepers are needed, whether to the particular countries that have experienced high levels of violence or they may be stuck in an office doing administrative work. We talked to decisions makers in the Bangladesh military, for example, who while they have sent all female contingents through their police, said they do consider the safety of women when deciding where to deploy women in the military.

JDG: There are gender imbalances in most security institutions around the world. How does this impact the participation rate of women in UN peacekeeping missions?

SK: One of the common reasons that the UN and contributing countries will give for sending more women is that they simply don’t have women in their military and police forces. While this may be more likely the case for the military, it is not the case for police. We aggregated data on the proportion of women in police forces and in militaries globally and then looked at whether or not the police forces around the world that had higher numbers of women are the ones contributing more to UN peacekeeping operations and they are not. There is something else going on for police contributions. We did find a correlation for military contributions. That is, the more females present in a contributing country military force, the more likely they are to send women to missions. We think this is because most military contributions occur through troop contributions, and women are either in units or they are not. In contrast, for police contributions, and perhaps military observers, women usually apply or are selected, which means that the number of women in the police force matters less.

JDG: Once the few women are deployed, do they experience discrimination in missions?

SK: While allegations of SEA receive a lot of coverage, what is not talked about is the experience of women in UN peacekeeping operations, including the discrimination and harassment many face. I don’t think I have ever seen any articles in the media or studies looking at the experiences of female peacekeepers and this is one of the bigger contributions of the book. These problems are symptoms of a broader cultural problem that all of societies are facing. It is exacerbated in the military and police because certain masculine traits are privileged over feminine traits in these organizations. Men are seen to be natural warriors and more competitive, whereas women are seen to need protection. If feminine traits such as the ability to listen, communicate, and empathize were equally privileged we would have equality in culture.

JDG: The case study on the UN Mission in Liberia (UNMIL) is one of the unique things about your book, what did you find when studying the experiences of women in peacekeeping in that mission?

SK: UNMIL provided an ideal study in terms of women’s experiences and I was able to interview a diverse set of women. It is touted as one of the more successful cases of women’s integration into peacekeeping missions because of the all-female police unit that was deployed there in 2007. My favorite part about writing the book was getting to spend a lot of time with female peacekeepers and learning about their lives and experiences in the mission and back in their home country. It was eye opening to me to learn a little about the uphill battles that they face in their jobs and the amount of optimism they have about what they contribute to the mission. Globally, they are sent to safe missions and not where they are needed. Once deployed, they are often further restricted in their movements. In the peacekeeping mission, the number one complaint, almost unanimously, was the lack of mobility and their inability to engage with communities. Sometimes it was because it wasn’t part of the mandate or their job description, but there seems to be a discrepancy between what the women in peacekeeping page on the DPKO website says versus what is actually happening on the ground. It assumes there is a lot engagement between female peacekeepers and locals and this is just not the case. It is not happening and it is the number one complaint of female peacekeepers.

JDG: What stories stuck out about the lives of women in this mission?

SK: I befriended a number of female peacekeepers and heard about their stories and a few of them stick out in terms of discrimination and even humiliation. There is one female from a sub-Saharan country who was the highest serving woman from her country. She was assigned as the deputy to the civil military division, where there was a Western male colonel in charge. She didn’t necessarily have the exact computing skills that he needed, but instead of using her for the skills she did have he would constantly set her up to fail and humiliate her in front of other peacekeepers. He would make her do presentations that she was unprepared to do and the talk behind her back and make everyone laugh at her. I saw this and it was very painful to watch. She was the only woman in that entire unit.

Outside of the mission, when women are engaging with locals, such as the female police officers assigned to train the domestic police force, they have to deal with borderline harassment and humiliation. A few of them would complain they would often get marriage proposals and were not taken seriously by their local counterparts. Then there was the problem of “Old Boy’s Networks” and the ability of men to socialize after hours, but not women due to rules and lack of access to vehicles etc.

I was surprised to find that women were also part of the problem. In the book, there is a story about this initiative in the mission where the female military and police officers, one of whom was a gender focal point, wanted to get together to do a community project with females living in an ex-combatant community. More senior women in UNPOL shot the project down as they felt they had not been properly included in the process. It is not just a case of men versus women, it is a culture and so women can be oppressive to women as well. The idea is to change the culture.

Gender Equality In UN Peacekeeping Operations Needs More Than Just Increased Women's Participation; There Needs To Be Cultural Change.

JDG: And what are some of the differences you observed between male and female peacekeepers?

SK: Despite all these challenges, the women unanimously believe they make a unique difference in missions, they believe they add value, and they were very optimistic about their role. The motivations for women to join peacekeeping missions and even the militaries and police back home were different for women and men. Whereas men often talked about the money and promotions as a reason for serving with a UN peacekeeping mission, women talked about helping people and going on an adventure. I did see the unique things women could do in a peacekeeping mission. I went on numerous patrols and one time I witnessed a female UNPOL peacekeeper mediate between two male LNP officers and a rape victim. There was a genuine effort by this female officer to resolve this case and when I interviewed her later she recalled how she had intervened as she felt solidarity with this woman.

JDG: And how did local people perceive female peacekeepers in Liberia?

SK: It is another innovation of book that we looked at local perceptions of women peacekeepers. Generally, there is a failure to take public opinion into consideration when we think about peacekeeping effectiveness. With fewer women in peacekeeping operations because of the barriers to participation, it is a little harder to gauge what is the reaction to female peacekeepers because of their lack of visibility. In our survey, there is some limited evidence that there is a preference for female peacekeepers and they are perceived as better. The survey was only done in the capital Monrovia and not the entire country, but in the city, most Liberian women did not have contact with female peacekeepers. There is very little contact and we debunked an assumption made by the UN that just because you have female peacekeepers they communicate with local women and the problems will be solved. Yet, there are definitely contributions made by female peacekeepers at the local level. Female peacekeepers also participated in institution building roles with the Liberian National Police. They were instrumental in developing the gender and the women and children’s protection units as well as the LNP’s sexual harassment policy. While the public interactions may be limited, behind the scenes there are many things going on.

JDG: Does this all add up to Resolution 1325 actually being implemented or is there a lot of box ticking going on without any of the culture change that you’ve argued needs to take place in UN peacekeeping missions?

SK: I am a little bit of a pessimist when it comes to this question. Similar to when it comes to different trends throughout the 1990s such as good governance and democracy promotion, I fear that gender equality might be another one of these trends and just be another box to be ticked. I see this because of the kinds of indicators that are reported. It is the number of women. This is something that can be easily counted. We make this point in the book that the focus on women’s participation is the only thing that has concretely manifested itself through UN Security Council resolutions through time with respect to gender and peacekeeping. We critique this point out that it is not just about women’s participation but real change means changing the culture of peacekeeping missions. For example, there is a common assertion, even in the Zeid Report, that increasing the proportion of female peacekeepers will lead to reduced levels of sexual exploitation and abuse by peacekeepers. This is simply not the case. Instead, in the book, we find that when there is a norm of gender equality in missions, it is likely to have fewer allegations of sexual exploitation and abuse. For this reason and many others, it is important to focus efforts and reforms on cultural change. This is not to say that we shouldn’t focus on operationalization or increasing the number of women in peacekeeping and in senior positions, but it is more than that and this is what the book focuses on.

JDG: How do we bring about this cultural change in missions?

SK: One of the reasons this is so difficult is that changing culture is nearly impossible to measure. The recommendations from the 1325 Study or the HIPPO report are important but they are sweeping. In the book, we focus on the smaller things that can be done to chip away at this culture. There are five areas where there is room within missions to start changing this.

First, there’s leadership. No change will be possible without strong leadership, especially in the military and police. There needs to be care about how SRSG’s, Force Commanders, and Police Commanders are selected with an eye towards gender equality. They obviously have to have certain qualifications to be considered for these positions, so why not include another standard for what they need to do to demonstrate how they have implemented gender mainstreaming in their own country or in their career. Questions can be asked at an interview stage about what have they done to address gender issues in their own institution? If missions have the right leaders, there should be a trickle down effect. If the force commander or police commissioner values this idea then it can be mandated down the chain of command.

Second, there can be changes to standards of recruitment as well as standards more broadly. Thinking about equality between traits. Right now, there is a privileging of recruitment based on masculine traits. Biologically, there are height, weight, and strength requirements to enter the military or police. There are sociological traits such as particular skills that you have to have that are all gendered male one related to rationality or over-confidence—think of the values of an “alpha male,” but if we also considered traits that are feminine, such as how well people listen, communicate, and empathize, these could also be included in recruitment. There are driving tests and computing test for peacekeepers, so why not test for gender equality or these other skills such as cooperation, listening, and communication that are needed for peacekeeping.

Third, there is promotion and demotion. It is very difficult to punish somebody who has committed sexual exploitation and abuse in a mission. They often just get sent home and there is usually no trial. Getting sent home can be a punishment in itself but there are still other ways to punish and promote good behavior for smaller offences. For example, lucrative placements can be used as an incentive for good behavior. Peacekeepers will request particular placements, especially for police or military observers. Awarding particular placements could be one way to leverage good behavior. Mission extensions could be used in similar fashion. Also not giving medals to certain people and being more selective about this. The UN has started naming and shaming contributor countries. There is more leverage for promotions and demotions within missions and it is important to find those levers.

Fourth, there are role models, mentors, and networks. This is focused on empowering women within missions. If you want to increase women’s participation and help women up the ladder, then women are more likely to apply for positions in a peacekeeping mission if they have a mentor to help them through the process. This is an alternative to the old boys networks that have developed in peacekeeping missions.

Lastly, there is training and professionalization. This is something that is kind of happening with regards to gender and peacekeeping missions. There is one unit in the two-week training on gender mainstreaming, but that’s about it. It is not done in the best way. It shouldn’t even be singled out as its own module, but rather integrated into every module and then it might be taken more seriously. Those kinds of trainings should be done with the Force Commander or other leadership should be involved with it so that participants can see that it is a serious matter. Moreover, one of the reasons that women are prohibited from joining missions is that they don’t have the skills with computers, driving a stick shift (manual transmission vehicle) or using a weapon. Professionalization programs for women in contributing countries are helpful to show they have the same skills as men. The Nordic countries, for example, have training program specifically for women of militaries and police forces in places such as Ghana. They could be an example for the rest of the world.

JDG: For those us working on peacekeeping policy and public debate as well as those of us in the media, how might we have more nuanced discussions about gender and peacekeeping? What mistakes might we be making in the way we talk about this issue?

SK: Most of the mainstream media reporting on gender is about sexual exploitation and abuse. This is what makes the front-page news. Moving away from this and the trope of women’s participation and delving deeper into the questions. Rather than simply reporting there are not enough women, they should be delving deeper into what is going on. The story is much more nuanced than there just aren’t enough women in the military and police in troop and police contributing countries. They should be asking: Where are women going on peacekeeping operations, what are they doing there, and what are their experiences when they get there? We want to pick away at the barriers they face. I don’t think I have ever seen a story about women’s experiences on mission. We see that peacekeepers can be predators against local women but we don’t see that female peacekeepers are also facing challenges such as harassment and discrimination. It would be interesting to bring peacekeeping voices to the media instead of just policy maker voices. There needs to be a broader discussion about the quality of peacekeeping missions. Peacekeeping effectiveness is not just about gender and peacekeeping. Because there is so much fear in DPKO that they cannot get enough troops and police from contributing countries they don’t want to criticize any country or draw attention to any problem otherwise they won’t contribute. There is a fear of moving towards quality peacekeeping at the expense of quantity. I have been surprise there haven’t been any in-depth investigations into those countries that are listed since 2015 on the naming and shaming list. If they name and shame these countries, then they won’t contribute to peacekeeping anymore and that will be a problem.

JDG: In an era when peacekeeping is shrinking in numbers, does it give you some optimism that this might be the time to focus on quality rather than quantity?

SK: I commend US Ambassador to the UN Nikki Haley’s goal to reform peacekeeping as long as it means not taking away resources from valuable programs and reducing the size and number of missions that are important. This is a good time for peacekeeping reform of all kinds and I hope reform includes equal opportunity peacekeeping because it creates a much more efficient system. If women are prevented from doing the things that they want to do and they are capable of doing, then they are not making as much of a difference as they could because of the barriers that I have mentioned. If those barriers are taken away, it will make peacekeeping more efficient and more effective. To improve women’s participation in missions, cultural change is needed, and this is what equal opportunity peacekeeping is all about.

Sabrina Karim will start a new job as an assistant professor in the Government Department at Cornell University in the fall of 2017. She is currently a U.S. Foreign Policy and International Security Fellow at the Dickey Center for International Understanding at Dartmouth College. | Twitter: @sabrinamkarim

Jim Della-Giacoma is the Deputy Director of the Center on International Cooperation and Editor-in-Chief of the Global Peace Operations Review. | Twitter: @jimdella