Array

(

[thumbnail] => https://s42831.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/hero-fpo-150x150.jpg.optimal.jpg

[thumbnail-width] => 150

[thumbnail-height] => 150

[medium] => https://s42831.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/hero-fpo-300x150.jpg.optimal.jpg

[medium-width] => 300

[medium-height] => 150

[medium_large] => https://s42831.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/hero-fpo-768x384.jpg.optimal.jpg

[medium_large-width] => 768

[medium_large-height] => 384

[large] => https://s42831.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/hero-fpo.jpg.optimal.jpg

[large-width] => 1000

[large-height] => 500

[1536x1536] => https://s42831.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/hero-fpo.jpg.optimal.jpg

[1536x1536-width] => 1000

[1536x1536-height] => 500

[2048x2048] => https://s42831.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/hero-fpo.jpg.optimal.jpg

[2048x2048-width] => 1000

[2048x2048-height] => 500

[gform-image-choice-sm] => https://s42831.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/hero-fpo.jpg.optimal.jpg

[gform-image-choice-sm-width] => 300

[gform-image-choice-sm-height] => 150

[gform-image-choice-md] => https://s42831.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/hero-fpo.jpg.optimal.jpg

[gform-image-choice-md-width] => 400

[gform-image-choice-md-height] => 200

[gform-image-choice-lg] => https://s42831.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/hero-fpo.jpg.optimal.jpg

[gform-image-choice-lg-width] => 600

[gform-image-choice-lg-height] => 300

)

The recent UN peacekeeping missions in the Congo are notable for their size and longevity.

In 1999, the UN Organization Mission in the Democratic Republic of Congo or MONUC was mandated to monitor the Lusaka Ceasefire Agreement. In 2010, it was transformed into the UN Organization Stabilization Mission in the DR Congo (MONUSCO), now the largest and most expensive peace operation, with 22,498 personnel and an annual budget of $1.2 billion.

©Congo Research Group

These missions have also been a critical laboratory for innovations in peacekeeping, especially with regards to the protection of civilians. Concepts such as Joint Protection Teams (JPTs) were pioneered in the Congo, and the mission experimented with various kinds of robust peacekeeping in Ituri and the Kivus, most recently with the Force Intervention Brigade (FIB).

However, since the 2006 elections and the end of the Sun City peace process, the mission has been marginalized from what it did best: the implementation of a political process. In 2010, it was transformed into a stabilization mission, mandated to help strengthen the Congolese and to protect civilians in imminent danger. Unfortunately, these two imperatives have often been at loggerheads. The government security forces with which MONUSCO has partnered have proven to be extremely abusive, and members of the army have backed other armed groups in the eastern Congo. What should the UN do when the same army it is sent to support abuses the civilians it is supposed to protect? Meanwhile, the mission has been unable to broker an effective peace process to deal with the remaining 70 armed groups in the eastern Congo or to play a critical role in bringing an end to the political turmoil in Kinshasa.

The blue helmets are especially unpopular in the very areas where most of them have deployed

It is in this context that the Congo Research Group (CRG) at the Center on International Cooperation set about to understand how the people feel about the mission that is supposed to serve them. The Bureau d’Études, de Recherches, et Consulting International (BERCI) and CRG conducted a nationally representative political opinion poll across the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Between May and September 2016, researchers interviewed 7,545 people in face-to-face interviews. This survey should be seen as complementary––and many of our findings were similar––to the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative’s surveys in the Congo.

We asked many questions, but the main ones related to MONUSCO were:

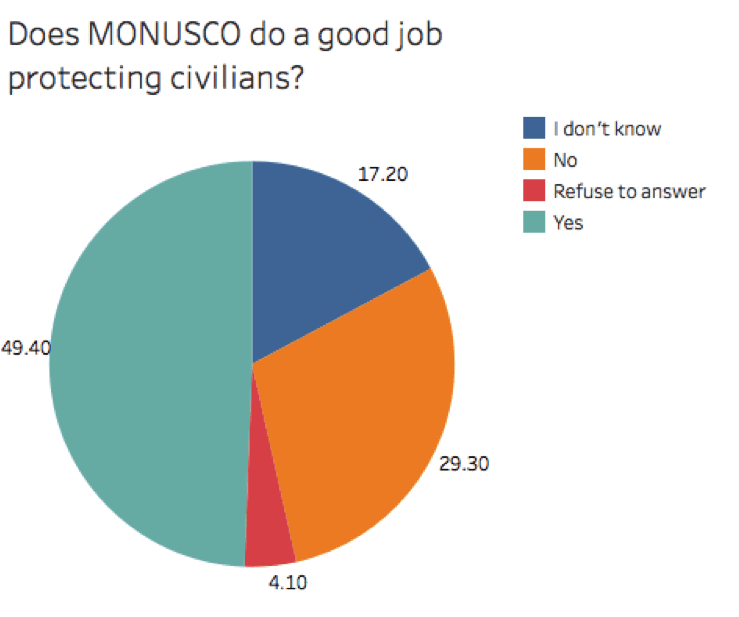

- Is MONUSCO doing a good job at protecting civilians?

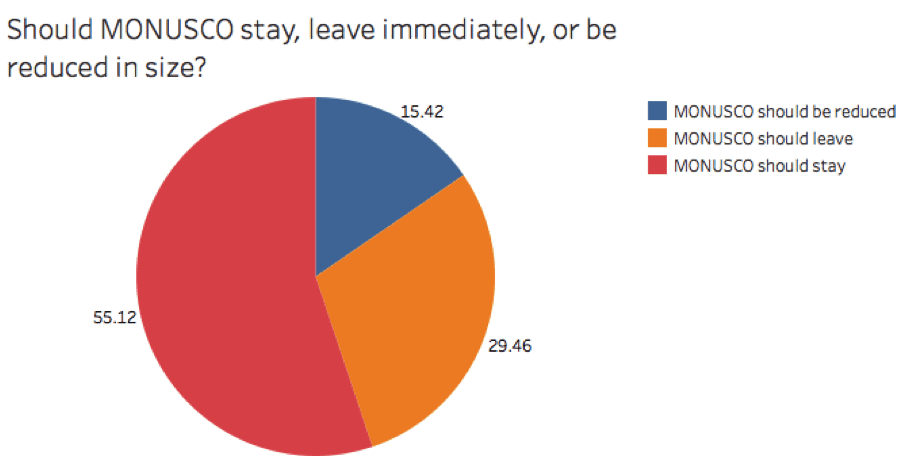

- Should the mission downsize, stay, or leave?

- Is MONUSCO corrupt?

General public opinion is mixed regarding MONUSCO: 55.1 per cent think the peacekeepers should stay and 29.4 per cent think they should leave. But the blue helmets are especially unpopular in the very areas where most of them have deployed: in Nord-Kivu (56.7 per cent), Sud-Kivu (50.2 per cent) and Ituri (45.2 per cent) a preponderance of respondents said the UN mission should leave. An alarming high number of Congolese also felt that the peacekeeping mission was very corrupt (17.4 per cent) or slightly corrupt (an additional 18.5 per cent). Only 36 per cent felt it was not at all corrupt.

People also felt that the mission should not wait for government approval or partnership to attack armed groups. Around half of those asked said the mission should engage in unilateral operations against armed groups who pose a threat to the local population, while 29.2 per cent said it should not.

How should we interpret these figures? What should the mission do? MONUSCO has always suffered from the problem of excessive expectations and the poor popular understanding of its mandate. The mission cannot be everywhere at the same time, and carrying out an effective counterinsurgency is dangerous and extremely difficult. At the same time, the mission’s failings, especially in the area of civilian protection have been well-documented. Other parts of our poll can help us analyze this data.

First, MONUSCO is not alone in terms of Congolese antipathy toward foreign actors. Many Congolese feel that they do not benefit from foreign aid, private sector investments or humanitarian work. We asked whether the Congo would be better off without foreign aid––31.3 per cent said yes. Similarly, high levels said the country would fare better without international NGOs (33.4 per cent) and foreign investment (31 per cent). Surprisingly, these responses are even higher in some of the provinces most affected. For example, in Nord-Kivu, which sees most activity by international NGOs, 47.2 per cent said they would be better off without them.

© Congo Research Group

Secondly, Congolese have a remarkably sophisticated understanding of their political situation. Overwhelmingly, Congolese felt that elections should be seen as the priority. We asked: “The country is facing numerous challenges, including poverty, a complicated electoral process, and violent conflict.” Respondents then replied whether security and development should be prioritized over elections, go hand in hand, or elections are more important. The results were clear: most respondents (46.7 per cent) felt all three are linked and should be worked on at the same time, 39.1 per cent said elections were more important than any other consideration, and only 14 per cent said security and development are a greater priority than elections.

The takeaway is that MONUSCO and the UN Security Council should redouble efforts to find a solution to the crisis in Kinshasa. If there has been one lesson from seventeen years of peacekeeping and stabilization in the Congo it is this: Without an accountable and willing government as a partner, it will be extremely difficult for the UN mission–as well as other foreign actors––to make any headway.

The complete survey report can be downloaded here.

More Resources

-

-

Reflections on the 2025 Peacekeeping Ministerial

Eugene Chen

Stay Connected

Subscribe to our newsletter and receive regular updates on our latest events, analysis, and resources.

"*" indicates required fields