Liberia is nearly, but not quite ready, to go it alone without United Nations (UN) peacekeeping support. This was the upshot of the 23 December 2016 UN Security Council (UNSC) meeting, where it was decided that the UN peacekeeping mission in Liberia, of which the mandate had expired, would be extended until March 2018 for the final time.

Since the end of its devastating civil war in 2003, the country has made significant headway in consolidating its peace.

The Liberian National Police has slowly taken over the security sector from the United Nations Mission in Liberia (UNMIL); there have been efforts to develop a stronger justice system; and the government has adopted policies and strategies designed to address the root causes of the conflict.

This year is particularly important for Liberia. It will conduct its first post-conflict, open-seat elections – and incumbent Ellen Johnson Sirleaf will hand over power to one of 22 political parties. It is unlikely that there will be one clear winner and parties will potentially have to form coalitions to gain a clear majority.

Already, allegations against some political party leaders have led to conflicts with the police. If the mudslinging witnessed so far is anything to go by, there is the potential that progress could be threatened.

The government’s ability to provide security is already being compromised by inadequate capacity. Security forces are stretched to their maximum: the government has committed to providing 8 000 police officers, but current figures are much lower at 5 101 personnel, of which 950 are women. An added challenge is the spread of resources. Monrovia receives a disproportionate allocation, while only 24% of police officers are deployed to the inaccessible, rural areas outside of the capital.

The decision to extend the UN peacekeeping presence in Liberia is therefore not surprising. Despite the pressure for Liberia to take full ownership of its peacebuilding challenges, recent field research has shown that UNMIL is still seen as a security blanket for the country. The presence of a continued UNMIL could act as a deterrent to those considering election-related violence.

At the same time, the United Kingdom, Russia and France – the three countries that abstained from the UNSC vote to extend the mandate (12 countries voted in favour) – have a point. As they noted, Liberia should now be focusing on peacebuilding activities, while UN mission resources are needed elsewhere, such as Mali.

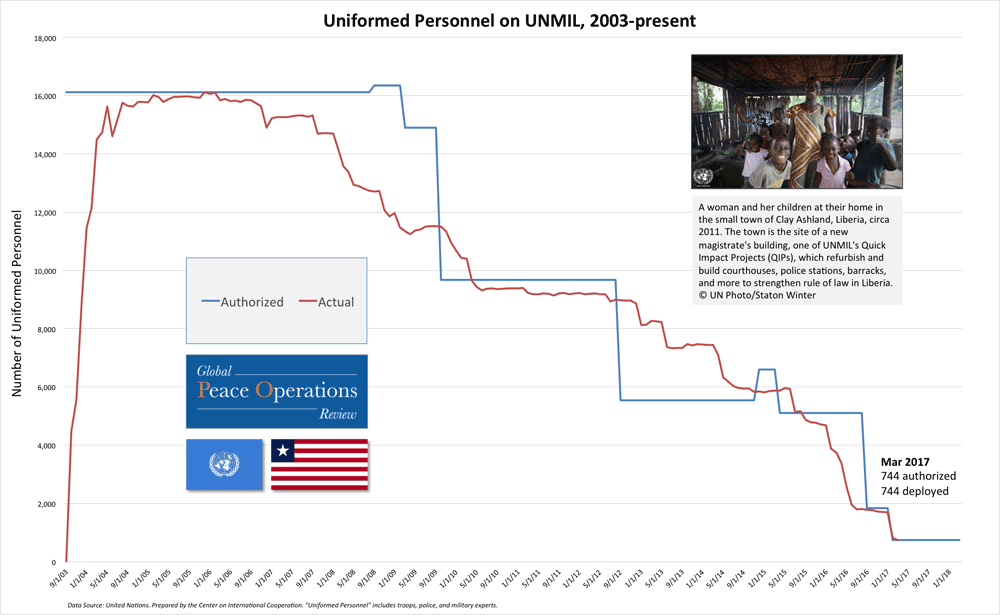

To be fair, the current new mandate is not very resource heavy: it caps the military strength at 434 personnel, and police strength at 310. This is a major decrease from the 15 000 military troops in 2007.

Moreover, as pointed out by the United States, Liberia’s institutions are still extremely fragile. There are high levels of corruption, and further capacity building is required. The Liberian government also requires logistical, financial and institutional support in preparing for elections.

While UNMIL can certainly assist in these activities, coordinated support from other actors could also be explored. For example, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) has a logistics depot in Sierra Leone, and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) has a programme for voter education that should be expedited and expanded as soon as possible, making use of civil society organisations in hard to reach rural areas.

Before the outbreak of the Ebola crisis in 2014, the country was well on its way in consolidating peace and development. The crisis diverted funds away from peacebuilding priorities, however, and presented new peacebuilding challenges. By late November 2015, the government of Liberia faced a myriad of challenges: from developing the economy to addressing national reconciliation. The same challenges remain and will have to be tackled even with UNMIL’s continued presence.

Liberia has limited revenue for providing basic services and is heavily dependent on donor assistance (including from the European Union, Sweden, the United States and the United Kingdom, to name a few).

Basic security and access to justice remains costly, and has not been adequately budgeted for by the Liberian government. There have been some efforts to decentralise the country to ensure greater localised ownership, but this has been hindered by the need for legislative reform. This kind of reform will allow for powers to be transferred from the national to the local, and subsequently for a Local Government Act to be promulgated.

More importantly, the underlying root causes of the conflict have not been adequately addressed. These include inter-ethnic divisions, lack of accountability and reconciliation, inequality and high levels of unemployment.

With the downsizing of UNMIL, other UN agencies (such as the UNDP, which is primarily focusing on voter education and decentralisation), now need to come to the fore. Liberian peacebuilding has been on the agenda of the UN Peacebuilding Commission since 2010, and has supported the National Peacebuilding Office in Liberia.

The Liberian government needs substantial support to prepare for elections

However, UNMIL’s presence has come to be accepted as the UN presence in Liberia – to the detriment of other UN agencies. The next imperative must be to educate the public on the UN transition, to create understanding that UN peacebuilding assistance will continue through other mediums.

In 2017, a focus on elections by both national and international actors is bound to detract from the need to deal with longer-term issues. The Liberian economy is suffering from the decline in commodity prices, such as iron ore, and Liberia’s development roadmap expired in 2016, – which is further complicated by the forthcoming change of leadership.

With interest and resources from donors waning both globally and also specifically for Liberia, how can a focus on the country’s peacebuilding activities be retained?

As noted in a forthcoming publication (part of a broader project carried out with partners the Center for International Cooperation in New York and the Peace Research Institute Oslo), Liberia’s peacebuilding efforts remain fragmented.

Civil society is uncoordinated and could better engage with the national peacebuilding office. Externally, donors do not often engage with bilateral African donors such as Nigeria and South Africa, nor do they engage fully with the African Union (AU) and ECOWAS on a coordinated peacebuilding strategy.

African regional, sub-regional and bilateral actors have much to offer, in particular because they emphasise national ownership, capacity building (through experience-sharing) and have context-specific models (such as, for example, on transitional justice). These may be very relevant to Liberia’s transition.

In 2015, a review of UN peacebuilding emphasised the need for peacebuilding solutions to be nationally owned. It also argued that the UN Peacebuilding Commission (PBC) play a stronger role in informing UNSC deliberations, by drawing on a wide range of perspectives – including those of African actors.

The PBC is now looking at new ways to work with the UNSC and play a coordinating role between different peacebuilding actors.

At the end of 2016, it organised a multi-stakeholder meeting in Liberia and a configuration meeting in New York, and conveyed findings to the UNSC. In addition, the PBC can also assist Liberians in mapping and capacitating civil society actors so that they can provide organised perspectives on peacebuilding priorities.

Yet, the PBC can do more to engage with the AU, ECOWAS and bilateral actors to provide a holistic and coordinated strategy, both for Liberia’s forthcoming elections and for its larger peacebuilding priorities.

Capacity building throughout Liberian society is vital for ensuring national ownership over peacebuilding solutions. This includes working with the political parties in developing their visions and strategies. In this regard, African actors can share experiences from the continent. African actors can also assist in adapting traditional systems of governance and practices, when state capacity is lacking.

Liberia has the opportunity to build sustainable peace. It will be important that UNMIL’s continued presence does not allow other peacebuilding actors to take the back seat. Peacebuilding in Liberia can be most effective if it is done in an inclusive manner, holistically supported by the international community.

This article was originally published by Institute for Security Studies on January 31, 2017

Amanda Lucey is a Senior Researcher, Twitter: @LuceyAmanda

Liezelle Kumalo is a Researcher, Peace Operations and Peacebuilding, ISS Pretoria, Twitter: @KumaloLiezelle

This ISS Today article was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and funding from the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The statements and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.