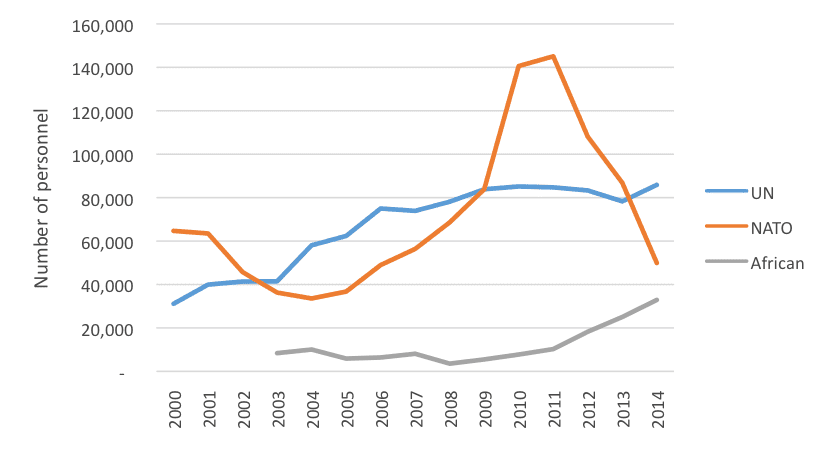

The last two years have seen a surge in peace operations. As the data in this review shows, UN deployments grew by 8.5% in 2013 and 2014 to involve over 100,000 soldiers and police officers. In the same period, NATO drew down its presence in Afghanistan but the number of personnel deployed by other regional organizations – primarily in Africa – leapt by 60%. There has also been a proliferation of political missions and special envoys dealing with conflicts: the UN and regional organizations appointed over 20 new high-level mediators in the last two years to deal with crises from Burkina Faso to Ukraine.

The first edition of the Annual Review of Global Peace Operations, published in 2006, opened with a statement that “the start of the twenty-first century has seen the resurgence of peacekeeping as a strategic tool.” The UN and its partners had recovered from the disasters of Srebrenica and Rwanda to mount a new generation of operations from Timor-Leste to Liberia. It was possible that this was a temporary phenomenon, but the Annual Review correctly predicted that this would not be the case: “there is every reason to believe that the demand for effective peacekeeping will rise, not shrink, in the years ahead.” Similarly, the first edition of the Review of Political Missions in 2010 argued that civilian crisis management operations “are a diverse tool, and demand for them is likely to increase.

As the Global Peace Operations Review website goes live for the first time, it seems safe to say that demand for peace operations will remain intense for the foreseeable future. Our strategic summary and global statistics on UN and non-UN operations illustrate major patterns in current deployments in more detail. Reviewing these figures, it is possible to identify ten key trends shaping peace operations landscape:

1. The United Nations Remains The Leading Force In Peace Operations.

Multiple organizations have contributed to the recent surge in peace operations. The AU and African sub-regional organizations have not only deployed emergency missions in Mali and CAR, but also expanded their political missions.

The EU has also expanded its role in Africa – launching its first military mission on the continent since 2006 in CAR – and the OSCE has leaped into the breach in Ukraine.

Yet the UN has remained the leading mechanism for managing peace operations. Globally, the UN is the largest single deployer of uniformed peacekeepers after NATO’s drawdown in Afghanistan. It has taken over the African missions in Mali and CAR, as its financial and administrative missions for running long-running missions remain more robust. It is also responsible for three-quarters of civilians deployed in peace operations worldwide.

These deployments do not always give the UN leverage: other actors have displaced it in orchestrating political process in Mali and South Sudan, despite the presence of thousands of blue helmets. But the UN’s leading role in peace operations remains resilient.

Figure 1: Total Military Deployments By Sponsoring Institution, 2000-2014

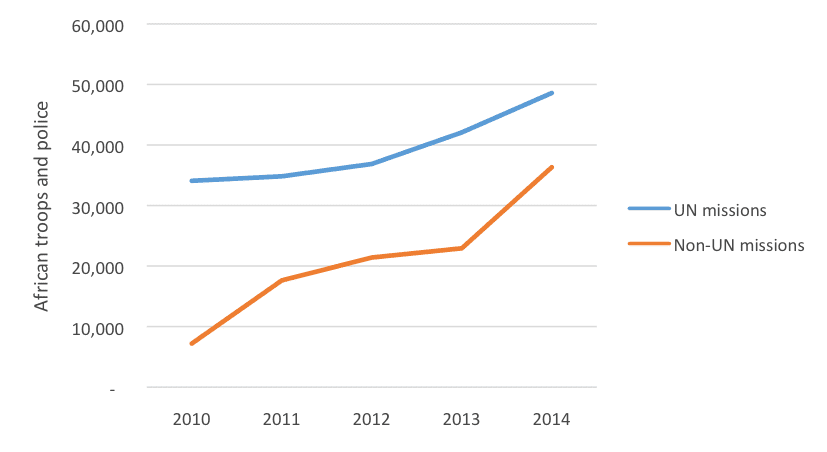

2. African States And Organizations Are Setting The Agenda On Their Continent.

Despite the UN’s continued institutional leadership, African governments and organizations are increasingly shaping peace operations on their continent, both through the UN and other channels. Their overall numbers of boots on the ground has expanded to 70,000.

The AU has sustained its mission in Somalia, gradually rolling back al-Shabaab in major population centers, and also took the lead in Mali and CAR alongside France while waiting for the UN to deploy. In the DRC, three African nations (South Africa, Tanzania and Malawi) contributed to troops to the innovative Force Intervention Brigade to neutralize militias.

African officials frequently argue that UN missions are too cautious and unwilling to use force. Both inside and outside the UN, African governments are likely to push for more robust and ambitious peace operations in future.

Figure 2: Number Of African Troops And Police Deployed In UN And Non-UN Mission, 2010-2014

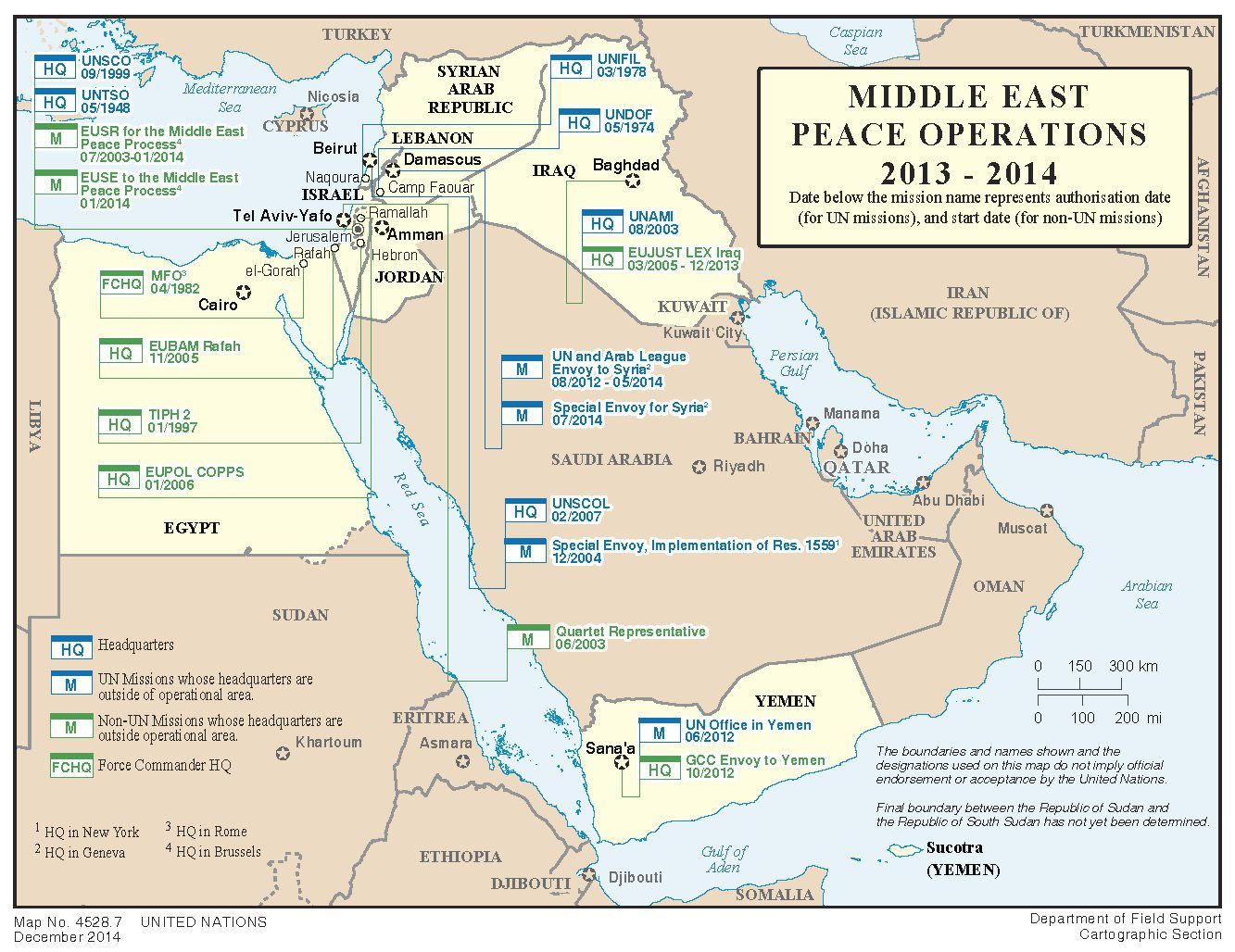

3. UN Operations Are Still Handling The Aftermath Of The Arab Revolutions.

While heavily engaged in Africa, the UN has had central role in the aftermath of the Arab revolutions in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), which have been a huge strategic challenge. Although it has blue helmets in Lebanon, on the Golan and Israel/Palestine, the UN’s primary contribution to the recent wave of crises has been political, through field-based political missions (as in Libya and Yemen) and the work of envoys (as for Syria).

These mediation efforts have often made frustratingly little progress. The Arab League has questioned the UN’s continuing role in the region, and proposed forming a stabilization force of its own. In Yemen, Arab states have opted military action over diplomacy.

Nonetheless, the UN’s central role in the MENA region has highlighted the importance of its civilian crisis management efforts and the need to strengthen them.

4. Robust Military Deployments Have Proved Effective But Hard To Sustain.

There is increasing political pressure for peace operations to use significant force to create stability. There is also evidence that they work.

In the CAR joint French-African operations probably prevented a genocide in late 2013 and early 2014. The African Union has continued to make advances against Islamist extremists in Somalia, creating space for the national authorities and UN to build a sustainable political system. In the Eastern DRC, the FIB succeeded in reversing militia advances in 2014.

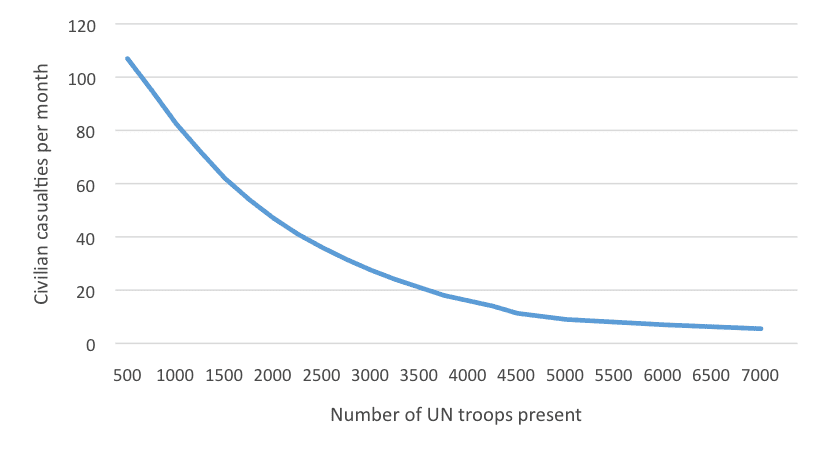

These successes parallel recent academic research that shows that the presence of peacekeepers significantly limits fatalities even where violence continues, and can successfully limits violence against civilians (see Ben Oppenheim’s essay). One recent academic study based on data from past missions concludes that the deployment of a force of around 7,000 peacekeepers can, on average, reduce civilian casualties to near zero:

Figure 3: Increasing Troop Presence Leads To Decreasing Civilian Deaths

However, peace operations often struggle to sustain these military successes. An internal UN report in 2014 found that many UN peacekeepers have not fulfilled their obligation to protect civilians in immediate danger. Extremist groups have inflicted frequently casualties on the UN operation in Mali despite France’s initial strong intervention. The FIB encountered difficulties in 2015 due to political differences over new campaigns and frictions with the Congolese army. It is clear that both the Security Council and troop contributors need to clarify their vision of the conditions for the effective use of force.

5. Civilian Political Missions Are Often Given The Highest-Risk Cases.

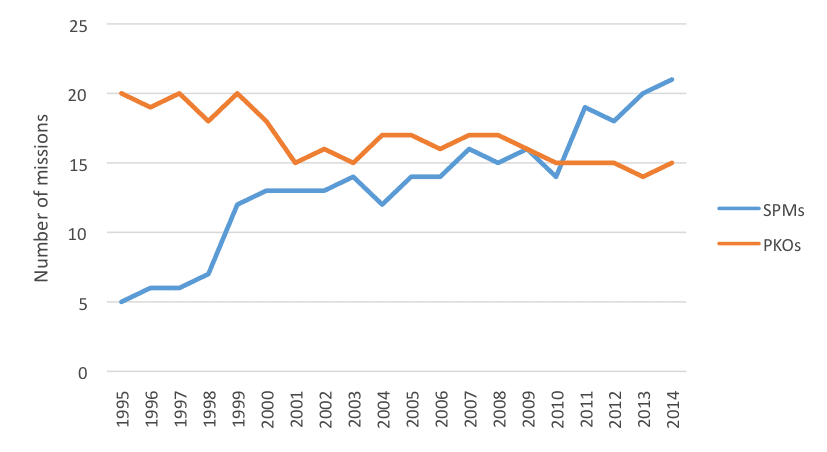

Despite the relative effectiveness of robust military mission, it often falls to light-weight civilian political missions to handle particularly dangerous cases. The Security Council has increasingly turned to political missions in recent years to respond to new crises.

Figure 4: Number Of New Missions Per Year, 1995-2014

Table 1: Political Missions In Countries Experiencing Major Civil Wars, 2009-2010 And 2013-2014

In Ukraine, civilian OSCE personnel have had to monitor a series of fragile ceasefires, and a number of OSCE teams have been kidnapped. In Somalia, Syria and Yemen UN civilian teams have also remained on the frontline of rapidly deteriorating conflicts – although the UN had to pull most of its staff out of Libya.

As the strategic summary notes, the Security Council has resorted to sending military guard units to protect civilians in cases including Somalia and CAR. There is a significant risk of “bunkerization”: UN personnel unable to fulfill their tasks due to security concerns.

6. The UN Is Struggling To Balance Its Portfolio Of New And Old Missions.

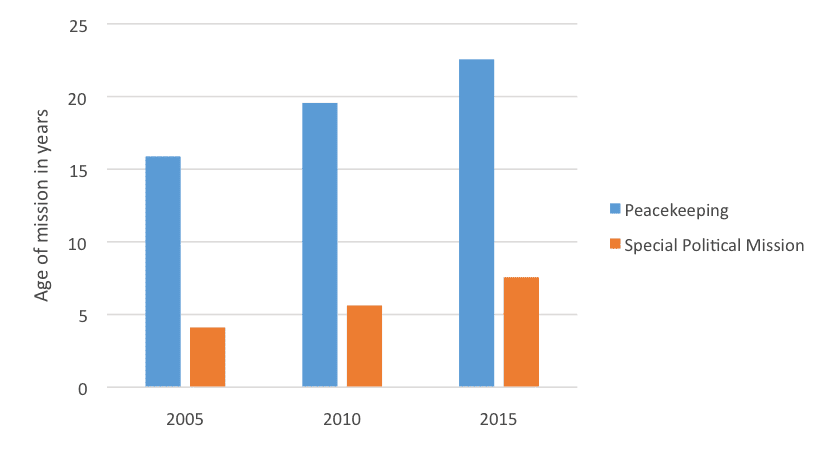

The UN has also had to face to the dilemma of launching new missions while sustaining large-scale pre-existing deployments. From 1945 to 1990, the UN launched 18 peace operations: an average of just under one every two years. Since 1990, it has launched an average of over three every year, (including both peacekeeping operations and special political missions). In recent years the overall number of UN peacekeeping operations has remained fairly steady –with roughly 15 in the field at any one time – while the overall number of political missions has risen (see Figure 6). But in the last two years the UN has had to launch two large-scale military missions (in Mali and CAR) while sustaining large-scale existing operations, including those in the Sudans, the DRC and West Africa. The average duration of both peacekeeping operations and political missions has notably lengthened in this period.

Figure 5: The Average Age Of Mission In Years (2005-2015)

Over half of all troops on UN missions are based in theaters where the organization has had a presence for over ten years. But many of these “legacy” missions are not ready to close.

The persistence of serious violence in cases such as South Sudan and DRC raise questions about the purpose of peacekeeping in these areas. Nonetheless, the Security Council and UN officials will need to search for alternative security mechanisms to large-scale open-ended peace operations – such as over-the-horizon forces able to deploy in a crisis.

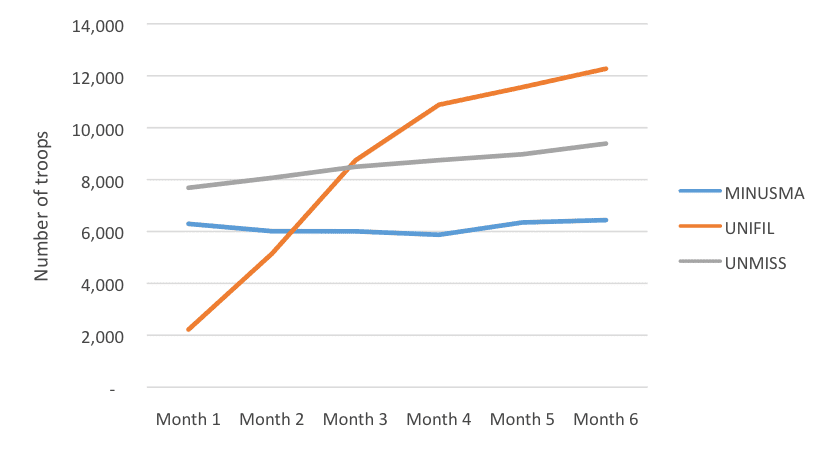

7. Peacekeepers Are Taking Too Long To Deploy To UN Operations.

With the UN so heavily deployed, there are worrying limits to its ability to respond flexibly and quickly to new crises. These include a mix of political and procedural obstacles to deploying new forces at speed. The UN mission in Mali, formally launched in July 2013, took six months to reach even a quarter of its planned strength. The Security Council mandated the UN to add 5,000 troops to the UN Mission in South Sudan in December 2013 – but the mission remained well below this target a full year later, severely limiting its credibility.

The UN has always had problems deploying its largest, infantry-heavy missions, but it can do better. When the Security Council mandated the reinforcement of the UN force in Lebanon in 2006, European nations got the troops on the ground in a matter of months.

Figure 6: Troop Deployment In First Six Months After Authorization

The slow processes in Mali and CAR highlight the need for the UN to develop more consistent rapid strategic deployment capabilities, both to launch new missions and reinforce old ones in crisis – or alternatively assist better-placed regional organizations to strengthen their rapid deployment systems as a precursor to blue helmet missions. While the AU was able to play this role in Mali and CAR, many of its units were short on the equipment they needed in the early phase of operations, and the missions were also prey to funding problems. These should not be allowed to hinder future deployments.

8. Western Powers Are Not Pulling Their Military Weight In Peace Operations.

As NATO has drawn down in Afghanistan, many analysts have hoped that Western countries will do more for UN peacekeeping – or support it indirectly through alternatives such as EU deployments. This support could fill many of the UN’s technical gaps.

There have been some positive steps in this direction: The Netherlands and Nordic countries have sent intelligence specialists and other high-end assets to Mali, and the EU has not only sent troops to CAR but also launched a number of civilian mission in the Sahel and East Africa.

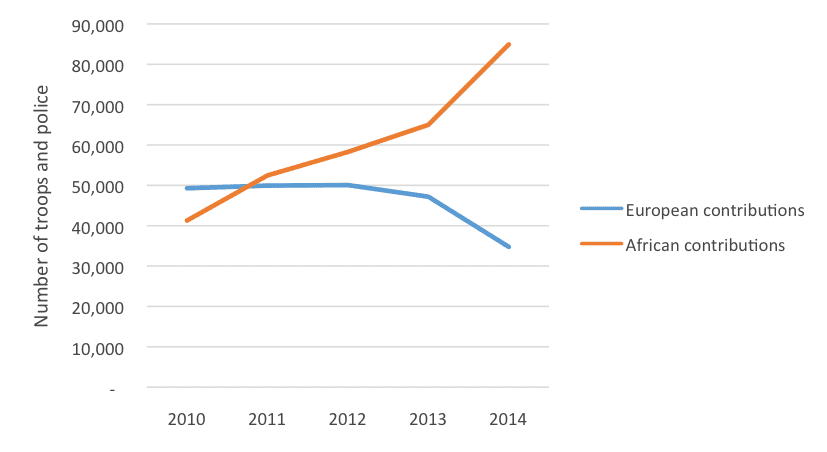

Ireland has played an important role in keeping the UN mission on the Golan Heights alive despite a series of kidnappings of peacekeepers by Islamist groups involved in the Syrian war. However, the overall trend in European deployments – both in UN missions and across all organizations — remains downwards. European nations are sending fewer peacekeepers to the Middle East and still avoid large-scale deployments in sub-Saharan Africa.

The US has recently called on its European allies to reverse this trend, and do more for the UN as part of broader transatlantic security cooperation. But the US still has fewer than 200 soldiers and police under UN command itself.

Figure 7: Number Of European And African Troops And Police Deployed In UN And Non-UN Missions, 2010-2014

While Western governments consider their peacekeeping options, South Asian countries (Bangladesh, India, Nepal and Pakistan) remain leading deployers of blue helmets.

China has deployed its first combat battalion to the UN (in South Sudan), expanding its overall contribution to the UN by 50%, and other regional powers including Indonesia and Vietnam have expressed their desire to increase their deployments. But for now their combined forces remain relatively limited – it will take a concerted strategic push by Asian powers to increase their participation in UN missions to match their rising global weight.

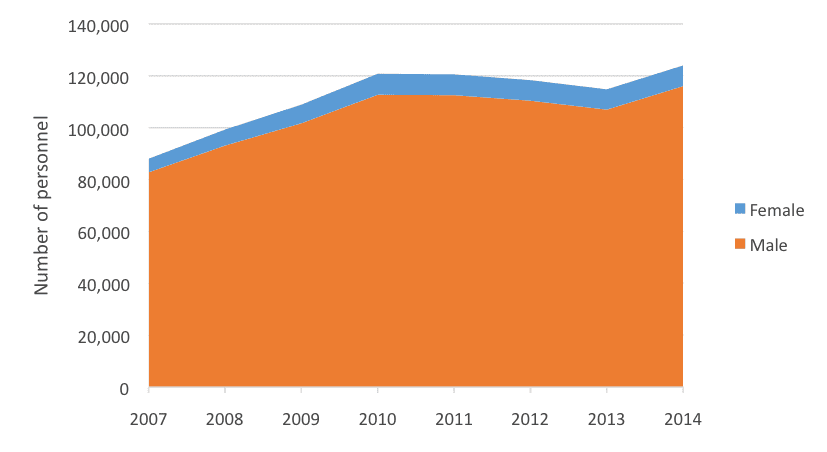

9. The UN Is Still Struggling To Get The Right Gender Balance In Peace Operations.

Despite a strong push for gender equality and mainstreaming by the UN Secretariat, a review of staff composition in UN peace operations reveals a continued gender imbalance. The gender gap is most pronounced for military personnel, where women in 2014 only accounted for three per cent of military staff in peacekeeping operations (see graph below).

Gender representation fared slightly better among police in UN missions, but women still only account for 10 per cent of police personnel. With 21 per cent, the most equal representation is among civilian staff in UN peace operations, although 10 years ago this number almost reached one quarter.

A more equal representation is also an issue among senior leadership in UN peace operations. Out of the 28 field-based peacekeeping and political missions active in 2014, only 7 were headed by women. There are improvements. The past year marked the first appointment of a female force commander to a UN peacekeeping mission (UNFICYP) as well as the occurrence of the first UN peacekeeping operation with a dual female leadership (also UNFICYP). With the High-level Review of Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace and Security commencing in October 2015 there is hope that the UN Secretariat and UN member states will recommit to increasing women’s participation in peace operations both on the working -and leadership level.

Figure 8: Gender Breakdown Of Troops In UN Peacekeeping Missions

10. There Is A New Spirit Of Innovation In Peace Operations.

Despite the many obstacles to existing and new peace operations, the UN and its partners have also shown a surprising capacity to innovate. The UN has mounted unique missions such as the UN-OPCW operation in Syria in 2013-2014 and the emergency relief mission to fight Ebola in West Africa in 2014. The UN has also made advances in using new technologies in its operations (see New Tools for Blue Helmets essay). The OSCE has shown a high degree of flexibility in monitoring the Ukrainian conflict. Peace operations are adaptable strategic tools.

There is still a political opening to strengthen peace operations of all types in 2015, and ensure that they can continue to meet the new burdens placed upon them.

Ban Ki-moon’s High-Level Independent Panel on Peace Operations lays out a framework for boosting UN peacekeeping operations and political missions, with an emphasis on conflict prevention and making mission more flexible, as well as improving cooperation with partners.

The High-Level Panel’s work has stimulated policy-makers in other organizations, including the AU and EU, to review their own thinking on peace operations in light of recent challenges.

In September President Obama will convene a summit on strengthening UN operations in New York, focusing top-level attention on the issue.

These initiatives offer a chance to address some of the main challenges to peace operations – including deployment times, robustness and the vulnerabilities of political missions – head-on. The recent surge in peace operations has demonstrated their continued importance to international security. It is now time to give them the support they deserve.

Download And Share The 10 Trends In Peace Operations Infographic